Reprinted from Massage Today,

June 2003 (Vol. 3, Num. 6)

P.O. Box 6070 Huntington Beach, CA 92615 •USA

|

|

The RamblemuseSMKeith Eric Grant, Ph.D. |

Training Effects

A three-and-a-half million year old foot print in East Africa, discovered by Mary Leakey, indicates that, by that time, our human ancestors had clearly diverged from the great apes. The footprint is of a creature unquestionably standing on two legs. The adjustment from walking on all fours to walking upright encouraged reliance on vision, and freed the front limbs for other work, like tool-making and carrying. The weight of the body, previously supported by the front limbs, shifted to the legs and pelvis, which thickened to carry the weight of the upper body. This, in turn, refashioned childbirth, causing babies to be born immature. — James Burke and Robert Ornstein 4

In exchange for more difficult childbirth and a long maturation time, we humans have gained more versatile bipedal mobility, dexterity and the freedom to express with our arms, and the upright environment and far-reaching vision that stimulated the development of minds that can strive for beauty in our movements. We are literally a species designed to move and, as importantly, one designed to adapt physiologically and neurologically to the movements we perform regularly.

As we learn a motor skill, such as massage or dance, we go through three identifiable stages. 1 We start our learning in a verbal-cognitive phase in which our attention is focused on deriving information on position and direction from demonstration and verbal direction. Our movements are typically created by joining together bits and pieces of our existing movement vocabulary. In the associative phase, we begin to develop focused movement patterns and continue to perfect and adjust them through practice. In the autonomous phase, movements are performed consistently with such precision and accuracy that there is little need for constant monitoring to insure correctness. We can literally turn our attention from the task at hand back into the surrounding environment.

|

|

|

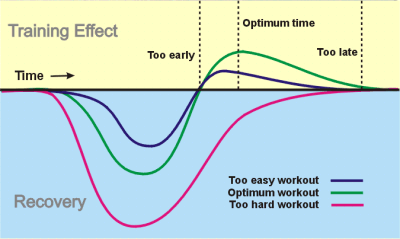

Figure 1: Soviet sports scientist N. Yakovlev's model of training and adaptation. After a workout, there is a recovery period followed by a period of super-compensation. The optimum time for the next workout is at the peak of super-compensation. Too early, and the body is still recovering. Too late and the benefits of the last workout are lost. The intensity of the workout must also be adjusted to achieve optimum training effect indicated by the blue curve. The recovery period will also depend on factors such as nutrition, hydration, and amount of sleep. |

In powering our movements, we have three different systems for obtaining energy that operate in a continuum. 1, 6 Immediate energy for high intensity movement, lasting up to 20 seconds, comes from the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) from creatine phosphate. Anaerobic glycolysis provides energy for high intensity exercise lasting from 20-180 seconds. Finally aerobic oxidation provides energy, quite literally, for the long run. With correct training, muscle cross section and muscle strength both increase. 1 Our abilities to use oxygen (VO2 max) and our abilities to process the lactate produced by glycolysis also increase. One of the most dramatic affects of including anaerobic intervals within aerobic conditioning is the increase in the intensity of exercise we can perform for extended periods, our lactate threshold. 2

Some years back, Soviet sports scientist N. Yakovlev devised a conceptual model capturing the concept of optimal training, both in intensity and repetitive timing, for maximum improvement (Figure 1). 5 If we train too hard for our current conditioning and recovery rate, we head ourselves into deepening fatigue and ultimately to breakdown. If we don’t train hard enough, we obtain too little benefit. The right intensity of training allows us to recover fully, and then to enter a period of super-compensation. If we train again at the maximum of super-compensation, we gain the greatest training effect. If we wait too long, we lose the benefit of what we did before.

|

|

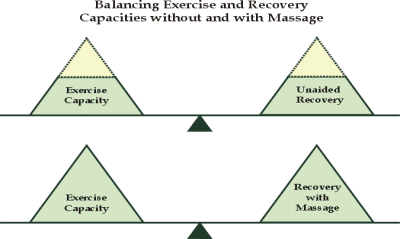

Figure 2: Exercise capacity and recovery capacity form a delicate balance. By normalizing hypertonicity, massage acts to increase recovery capacity. Increased recovery capacity allows increased exercise capacity, and a higher level of training. |

The benefits of massage come partly, I believe, in shortening the recovery time in Yakovlev’s model. As depicted in Figure 2, when recovery capacity is increased, exercise capacity can increase yet stay in balance. 7 Thus, we facilitate the gains of super-compensation. The mechanisms for this, I believe lie in the interactions between the psychological and neurological. Daniel Arnheim noted both aspects of staying focused and relaxed in discussing injuries in dancers. 3

The psychological aspect of injury prevention is as important to the dancer as is proper conditioning and nutrition. Dancers, like all people, have varying personalities and react to stress in unique ways. What sets dancers off as unique from other individuals is that they are artists seeking perfection in movement. … The extent to which the dancer can withstand the psychological stresses imposed by the dance environment is determined by the dancer’s total psychoemotional development and lifestyle, both past and present. …

When considering injuries associated with psychogenic factors, one must consider muscular tension as a major cause in the dance field. Tension is defined as increased muscular contraction as a result of some emotional state or muscular work. Nervous tension is a syndrome that is characteristic of the so-called fast way of life of our times. It is associated with anxiety that comes from an undefined worry or fear. An overanxious dancer can have an extremely high level of unneeded muscular tension. The person who is outwardly anxious may be less flexible and less able to smoothly coordinate muscles. Organically, he or she may have an increased heart rate and blood pressure. The tense dancer is extremely susceptible to injury and because of the increased muscular excitability may over-respond to painful conditions.

Viewing massage as an interaction and communication, we become part of the lifestyle structures of support to which an athlete and kinesthetic artist can turn. Beyond this, we can address the tension to which they might unconsciously cling.

Among the wonders of the terms of our human embodiment, is the astounding plasticity we have to learn new kinesthetic skills and to adapt our bodies to their impassioned pursuit. Among the wonders of the massage we pursue, is our ability to affect the training of those who come to us.

References

1. Abernethy, Bruce, Vaughan Kippers, Laurel Traeger Mackinnon, Robert J. Neal, and Stephanie Hanrahan, 1996: The Biophysical Foundations of Human Movement, Human Kinetics, ISBN 088011732X.

2. Anderson, Owen, 1998: Lactate Lift-Off, SSS Publishing Inc., Lansing, MI, ISBN 0-966-37260-3

3. Arnheim, Daniel D., 1991: Dance Injuries — Their Prevention and Care, 3rd ed., Dance Horizons, Princeton, NJ, ISBN 0-871-27146-X.

4. Burke, James, and Robert Ornstein, 1995: The Axemaker’s Gift — A Double-Edged History of Human Culture, Grosset Putnam, NY, ISBN 0-399-14088-3.

5. Eyestone, Ed, 2001: Model Behavior, Runner’s World, Sept. 2001, 32.

6. Knuttgen, Howard G., 2003: What is Exercise? — A Primer for Practitioners, Physician & Sprtsmedicine, 31(3), < http://www.physsportsmed.com/issues/2003/0303/knuttgen.htm>.

7. Ylinen, Jari, and Mel Cash, 1988: Sports Massage, Stanley Paul, London, ISBN 0-09-173746-X.